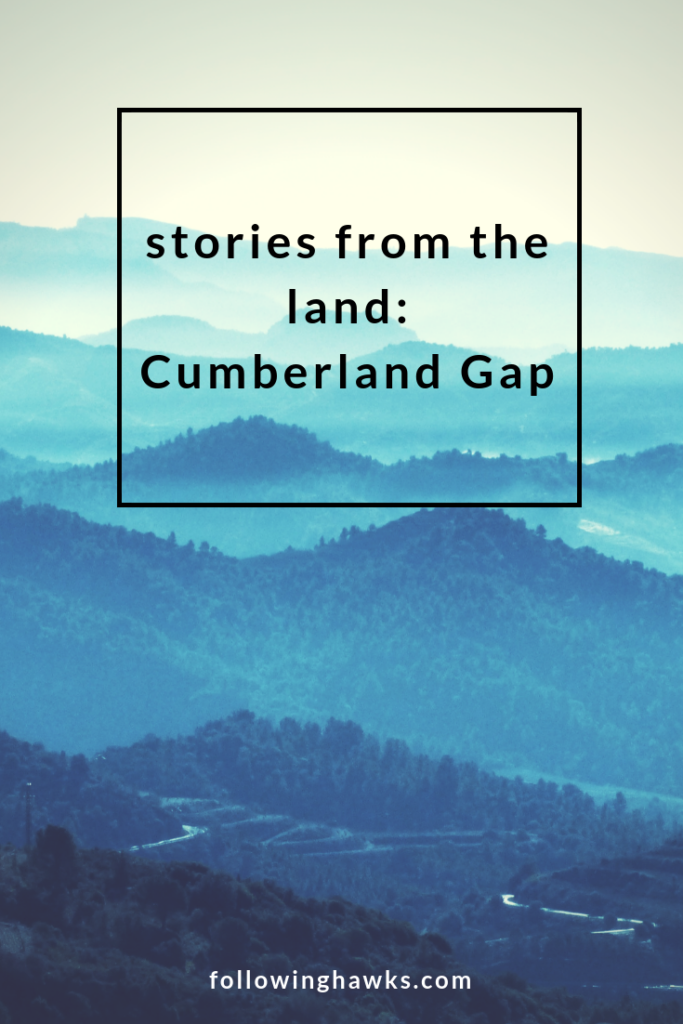

I'm only a few stories into telling the stories from the land and I've already figured out…I'm not in charge here. The stories are coming out on their own schedule, regardless of my requests. This week, I intended to connect with the areas of Whitesburg and Pine Mountain in the Cumberland Gap area of Kentucky, as suggested by Carla, one of the regular readers of my writing here.

I'll just spoil the suspense right now by saying that I was able to connect a bit with the land in the Cumberland Gap, but when I got to the specific areas she requested, the spirits said, “That's another story”. So I flipped the page in my notebook, readied my pen and said, “Okay, I'm ready, tell me.” And they said no, it's another story for another time, not now. And that was the end of it.

Umm, okay. Fine then.

So who did want to talk to me this week? Daniel Boone. Yeah, THAT Daniel Boone. I was as surprised as you are. And I have to be honest, since I grew up in California, most of my elementary school American settlement history was focused on the gold rush and the Oregon Trail, not earlier explorations from the colonies to the frontier lands of Kentucky. So my knowledge about him and his story was limited.

In fact, when I mentioned this to a friend (who also grew up in California), she said….I guess I don't know the difference between Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett. And I realized I didn't either. So yeah, “American frontiersman” was about the extent of my recollection of Daniel Boone's adventures.

For those of you in the same boat as me, and for the benefit of understanding what he shared with me in this reading, Daniel Boone became famous for this exploration and settlement of what is now the state of Kentucky. At the time of the American Revolution, it was still part of Virginia, but was on the eastern side of the Appalachian Mountains from most of the European-American settlements.

Despite some resistance from American Indian tribes such as the Shawnee, in 1775, Boone blazed his Wilderness Road from North Carolina and Tennessee through Cumberland Gap in the Cumberland Mountains into Kentucky. There, he founded the village of Boonesborough, Kentucky, one of the first American settlements west of the Appalachians. Before the end of the 18th century, more than 200,000 Americans migrated to Kentucky/Virginia by following the route marked by Boone.

However, when he appeared in my reading, he didn't show himself to me as a conquering hero. He was a small, old man with crumpled hat and wrinkled clothes. I asked why I was seeing him like that and he said that he now has the benefit of the wisdom collected throughout his life.

“We were great explorers!” he said, “It was an honor and an adventure, but I do have some regrets.”

As is all too common in our collective American history, Boone and his fellow explorers plowed through the area with their own agenda. He said that settlement of the new frontier was what was important. He was helping to build a nation and if it hadn't been him to blaze this trail, it would have been someone else.

But his regret still runs deep. He said that he was so focused on being first, that he wasn't concerned with what was right. He wanted the glory and pointed out to me that he is still remembered today. “But for what?”, he asked me.

He now sees that his methods could have been different.

Boone said that he could have been more gentle in his approach to trail building. He could have collaborated with other settlers, explorers and the native tribes in the area. In fact, he said, the tribes were generally helpful in the early days – they were accustomed to trading with the settlers. Instead, in their efforts to push ahead at all costs, the stories of the native people in the area have been wiped from the landscape needlessly.

After chatting with Daniel, I looked up more details about him online and his regret made even more sense. His family were Quakers who had fled England for Pennsylvania to escape religious persecution. However, after two of Daniel's siblings married non-Quakers and his father refused to apologize to the church for the transgressions, his family was kicked out of the church and they left Pennsylvania for North Carolina. It was while he was in North Carolina that he, along with 30 other woodsmen, were hired to blaze the trail through the Cumberland Gap – the only natural break in the Appalachian Mountains for 100 miles in either direction.

A few years later, after settling in Kentucky, he was captured by a group of Shawnees.

The Indians took him to their village in Ohio, where he was adopted by Shawnee chief Blackfish to take the place of one of his sons who’d been killed. Boone, who was given the name Sheltowee, or Big Turtle, was treated relatively well by his captors—he was allowed to hunt and may have had a Shawnee wife—but they kept a close eye on him.

Four months later, he managed to escape and make his way back to Boonesborough, where he warned residents that the natives, upset because settlers had moved onto their Kentucky hunting grounds, were planning to attack. That September, over the course of nine days and nights, a group of Shawnees and other Native Americans laid siege to Boonesborough, but the outnumbered settlers managed to hold them off. The victory at Boonesborough helped spark a new wave of emigrants to Kentucky, some of them personally recruited and led there by Boone.

Boone became a celebrity when a local teacher-turned-land speculator wrote a book based on Daniel's adventures to encourage settlement in Kentucky, but the stories were heavily embellished by the author. After Boone’s death in 1820, his legend continued to grow with the publication of such best-selling works as “The Biographical Memoir of Daniel Boone, the First Settler of Kentucky,” released in 1833. In this sensationalized account of Boone’s life, author Timothy Flint portrayed him as a ferocious Indian slayer who engaged in hand-to-hand combat and swung on vines to elude capture; in reality, Boone had friendly relationships with a number of Native Americans and claimed to have killed just a few of them.

So I can imagine why he might want to share his regret with us today.

How many people around the world were inspired to immigrate to America or across its frontier by larger than life stories like this? And it would have supported the government's Indian removal policies and propaganda of the day which ultimately attempted to erase the indigenous people, or at least their culture, from our landscape.

One of Boone's sons was killed by Cherokees and one of his daughters was kidnapped by Shawnees (she was rescued only a few days later in a story that inspired the author of The Last of the Mohicans) so it seems that he continued to pay the price for his adventures throughout his life.

He ultimately lost his land in Kentucky and moved his family to Missouri, which was territory claimed by Spain at the time, and remained there until his death.

I'm still working around in my head why this story was important to be told here. Does Daniel want to justify his actions or want us to feel sorry for him? Is he attempting to set the story straight? Is he telling a cautionary tale that is relevant to us today?

Or is he just another ancestor who needs healing for himself and his descendants?

I really wasn't expecting to be talking to many humans during this project. I thought we were going to be hearing from the land itself. But what I'm realizing is that these are the layers of pain still sitting on top of (or within) the land. We can't even get to the land without peeling back all of these layers first. It feels a bit overwhelming, to be honest.

And this is another point that continues to be clear. The land cannot heal itself until we choose to heal ourselves, our ancestral lines, and the pain that has continued for generations.

After my chat with Daniel, I did actually speak with the mountain at the Cumberland Gap.

It actually kind of creaked towards me and said…well it's about time someone asked ME what I think! The mountain explained that the passage located there was important to the expansion of civilization but that it sits under the weight of millions of footsteps. It understands its part in helping to carry people into the west.

The mountain had, at some point in the past, put protective energy over the trail to keep its energy separate from the travelers. It was attempting to avoid absorbing the energy of those who passed through. The mountain explained that there was much heartache associated with the settlers leaving behind their family and homes to move to the frontier and it didn't want those emotions attached to itself.

I explained that the pathway is no longer used in that way and the protective barrier is probably no longer necessary and it immediately shook itself, breaking up the barrier. I helped to send the remnants of that barrier back to source energy to be cleansed and the mountain seemed satisfied with our conversation.

As soon as I completed this reading, on Halloween afternoon, the power went out. It only lasted about 10 minutes and I later learned that it had gone out in almost every town in our county, simultaneously. I'm not even sure how that's possible and I doubt it was related to this reading. I joked on Instagram that it was an impressive, coordinated work of spirit to put us in the Halloween spirit.

But really, the veils are very thin this time of year. It's much easier to see and understand that there is little that separates us from spirit, which makes it easier to understand why this work with our ancestors and the land is so important. Just because we can't see it, doesn't mean it isn't there and isn't affecting our everyday lives. It's important that we continue to heal our ancestral lines so we don't pass along this pain and trauma to the next generation and we give them the opportunity to heal our collective relationship with the land.